Laure, now known as Laura, is my oldest friend. We met at kindergarten, aged three, in a school founded and run by a Madame Yanowska in Neuilly, just outside Paris. My parents had picked that particular school because it was different, something between the Waldorf and Montessori methods. Over the years I’ve come to believe that the magic ingredient in good schools is not so much an educational system as the fact that they are run by loving enthusiasts as opposed to unhinged sadists.

I have no recollections of the school itself save for a few mental snapshots: bright primary colors, intended to convey cheer but arguably just meaning, “You’re not at home”; the first of many such corridors papered with drawings, with hooks at two heights, one for small people, one for adults; little benches; a picture of my pretty teacher Mademoiselle Annie, with short black curly hair, looking like Georgina, the tomboy of the Famous Five; a gate through which we ran into the street while propelling wooden hoops with a little stick. I credit an early interest in physics to this hoop game. I still feel in my bones the part-docile, part-restive behavior of the hoop, capable of bouncing along happily when tapped at intervals, but falling into a dead faint when the gyroscopic torque ran out.

I was in love with Mademoiselle Annie, and had a screaming tantrum when her boyfriend came to pick her up at school. She took us skiing in the Alps, a bunch of four-year-olds carrying tiny skis. Those were different days, when some casualty, such as a broken leg or collarbone, was considered par for the course. We gathered at the Gare de Lyon to get on the train. My mother recalled that she and my father were very anxious for my first trip away. As it happened, the moment I saw my class and Annie farther down the platform, I ran off, skis on my shoulder and rucksack on my back, singing at full throat, without even saying goodbye.

A secondary purpose of special schools is to bring together parents of like mind, such as those who think their kids are special and best left to develop unhindered. (I imagine other schools might gather people who are fond of dressage.) Laure and I were inseparable. Naturally our parents became friends. Hers happened to be remarkable people, the writer Harry Mathews and the sculptor Niki de Saint-Phalle, both Americans. Harry was a prime example of an American in love with Paris while secretly horrified at the filth. He asked my mother, also a New World type, whether the tap water was fit for drinking, and he had his laundry done in London, driven back and forth by van.

Harry and Niki owned a large house in the Vercors region of the Alps, near Villard de Lans. They once invited us to spend Christmas there with them. I remember that as my best Christmas ever. Laure and I were conspiring to change the world, build a time machine, and steal a march on all dumb adults. We had discussions at a level of seriousness I have never reached since. Children are natural conspiracy theorists. In French they use the conditional to denote imagined things: on dirait qu’on serait (“we would say that we would be”). Children are also perfect mob material. They resonate to the ambient atmosphere like a glass organ.

Harry was perfect in this context. He was also a modernist composer and loved bad-taste classical music. He and I listened to Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld sufficient times to be able to sing a long duet together, to everyone’s delight. He was Diana, and I seem to remember I was Public Opinion. I have tried to find the passage we sang but cannot suffer through the whole opera.

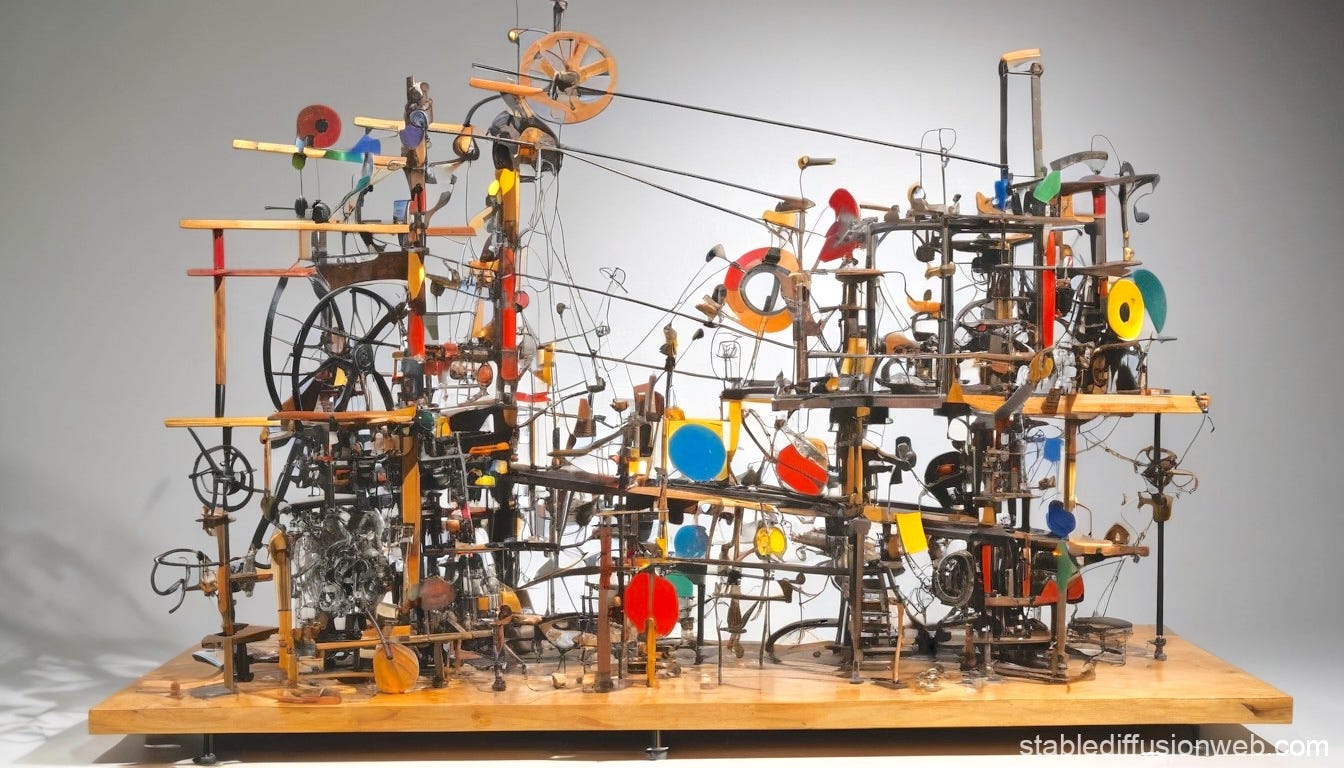

The living room had a wall sculpture by Jean Tinguely. It was a complex machine made of bits and bobs, mostly wire wheels linked to each other by belts and gears. There was a geared motor at bottom left, connected to the mains by a socket. When turned on, the entire thing was set in motion and made the most wonderful clicking and tapping noises, with the occasional hollow tock like a pinball machine giving you a free play. The mechanism looked aperiodic and likely would take a thousand years to repeat itself. I was prepared to wait, and sat in front of it for hours soaking in the rhythmic whimsy.

Niki spent most of her time in her workshop near the top of the house. We were not allowed in there, and like most artists she guarded her own space. In those days she was making wall sculptures out of plaster and papier maché built up around tins and spray cans of paint. She would then go to the other end of the room and shoot at them with a .22 rifle1. The cans would split open and leak or spray paint. This was all explained to me, and I think I even saw a couple of the finished products. None of it made much sense to a child, but the method carried an aura of anger and danger that commanded respect. Niki was largely invisible, and I have no recollection of meals with her present. My only picture of her is of a handsome, wide- and somewhat wild-eyed woman in a white turtleneck, sleek trousers, and short boots.

One night shortly before Christmas Day, Niki decided that the furniture that had come with the house was getting her down, and so naturally she started throwing it into the courtyard in front of the house from the upper floor windows. The rest of us assembled it into a pile, and Harry set fire to it. The place was huge, the furniture wooden and plentiful, and pretty soon we had a massive pyre burning brightly into the night. We children loved it, of course, wanton destruction being second nature to us. As we were dancing around the flames, the local fire brigade turned up from down in the valley with two engines, ready to douse what they thought was a house fire. I remember there being some awkwardness when it was explained to these austere Savoyards what we were burning.

My parents, I now realize, were largely invisible through this. I am not even sure my father was there, though I assume he must have been and likely disapproved of the reckless, rich-hippie atmosphere. My mother enjoyed it. The best part was a huge Christmas tree in the living room. We children got up early on Christmas morning while the grownups lounged in bed, and we opened what seemed like an absurdly large number of presents all by ourselves. We felt pretty certain that Father Christmas was real, because the local grownups clearly could not have managed it.

The fumes irreversibly damaged her lungs , and a spray can blew up in her face once, nearly blinding her.

I'm in envy of your glamorous Christmas, appalled by the wanton waste of good furniture, and curious as to whether the lung damage played any part in the creation of her famous eponymous perfume? There can't be two Niki de Saint Phalles, can there?

You must have tried the perfume - what did you think of it?