Who's there?

My year working with AI

I would probably use AI a bit less if I was ensconced in an Oxford college where, from time to time, at a lunch of sirloin béarnaise and overcooked beans washed down with an ‘82 Médoc, I could choose to sit next to an expert and pepper them with questions, all the while apologizing for my stupidity and ignorance. Instead, I pay AI a small monthly sum and can access all the expertise I want at all times of the day and night. However, I miss both the food and the sense of awe that comes from talking to someone whose life may have been very different from mine, but who nevertheless lives in the Republic of Ideas.

Another thing I miss while asking AI questions is the polling I used to get from classic Google search, where a question gets a range of answers. AI prefers to narrow your focus, like a dog straining at the leash to follow a scent. You can even adjust its mood and eagerness so AI will behave, for example, like a surfer dude—“Have an awesome day!”—or like a Cambridge reptile—“You find that interesting, do you?” We humans are suckers for mimicry. I remember in 1973, being taken to Arpanet’s first European “tip” in UCL’s engineering building, where I sat at a Teletype dialoguing with Parry the paranoid computer, finding it uncanny. The material world around us feels so inert that we greet any sign of sentience with joy. Current AI is of course vastly better, and different AIs have different personalities. I was trying to envision who I feel is in there talking to me. Claude comes across as an erudite and enthusiastic younger colleague, possibly with some edgy fashion choices: brightly colored socks, French workman’s jacket. GPT has a more austere, nerdy vibe: pocket protector full of pens, Hush Puppies. Generally speaking, I see a guy for sure, though this may be more my internal default value. I will try a more feminine overall setting to see if it makes a difference.

My fondness for AI is mostly due to the fact that I am a scientist working between two disciplines of entirely opposite character. In biology, AI’s strength is comprehensiveness. No one knows more than, say, 1% of the total facts1. The cabinet de curiosités created by three billion years of evolution is vast and we have only begun to catalog it. Insofar as AI has scanned every scientific article in the last 150 years2 it is a genuine know-it-all. You can ask questions like, “Are there instances of animals living in inflatable houses other than appendicularians?” and get an answer (“Pteropods and spittlebug nymphs come close”) that a Google search would not have found.

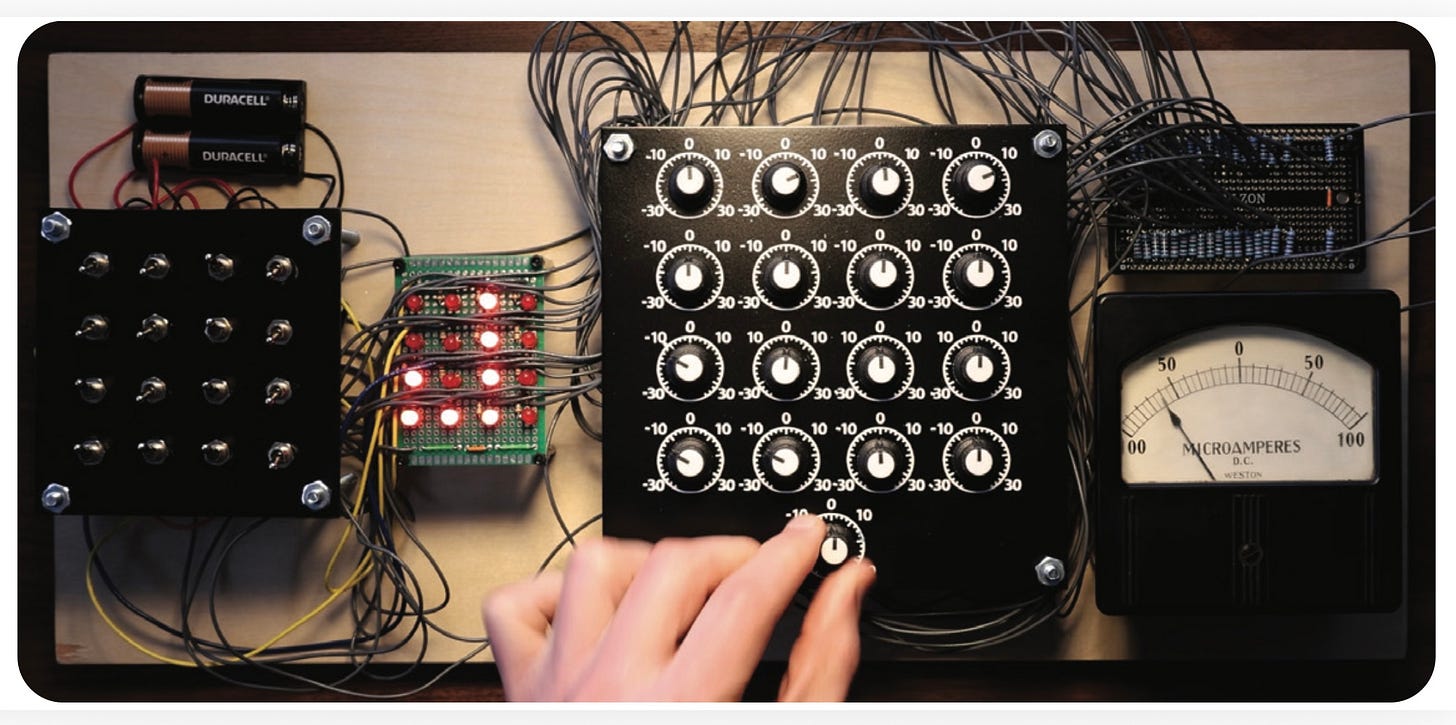

At the other extreme lies physics, where the rigid connectedness of facts is their prime virtue. AI can quickly write and run code based on the relevant equations, so it is now very good at extrapolating from one thing to another, and in particular, calculating order-of magnitude effect sizes in response to a hare-brained idea. If I ask the AI if something is possible, its answers can be set to any level of reality-distortion field, from “nothing new under the sun” to Murray Gell-Mann’s adage, “the best theoretician is the one who is wrong the fastest.”

A good-news–bad-news alternation is best. I believe in Salvador Dali’s Paranoid-Critical method, which says creativity is manic and criticism depressive, so therefore invention is necessarily bipolar. The more you pay for chatgpt, the longer it thinks and the more realistic its answers become. I therefore alternate between the cheap-euphoric and the expensive-dismal settings, to first dream and then devastate.

People complain about the garrulous delirium of AI, inventing books, awards and people. I personally think a touch of garrulous delirium is what makes a place liveable. The intellect has a Zurich and a Naples, and I’d rather have the views that go with the garbage. In years past, I even suggested we needed an automatic generator of really interesting and eccentric but totally fake scientific papers, to give people working on new theories some support. When on day one you ask, “Has anyone ever done anything like this before?” if the answer is no, not ever, it takes a lot of courage to pursue it anyway. Most new ideas simply die at that single-celled stage and never develop. I’ve long held the belief that there should be idea nurseries where the tiny saplings are protected from criticism by some small fictitious support until either they are strong enough to grow on their own or they wither. AI delirium serves this purpose nicely.

AI, conversely, is very good at clearing out weeds when asked. I’ve carried a few odd unexplained facts in my head for decades, saved for a day when I could finally work on them, do experiments, etc. These have acted as lucky charms, overgrown paths not taken, supplying the solace of what might have been. Lately I have been subjecting them to AI weeding. Only one out of five is left unexplained, as what scientists call a “retirement project.” I feel lighter and freer for it.

AI has decisively moved what I consider the main obstacle to human progress, the boundary between work and fun. It matters to me because I am constitutively incapable of work. Any trivial drudgery, such as collecting receipts of lab purchases to have them approved by finance, feels like a huge mountain to climb, even though it takes twenty minutes. Reading an instruction manual tries my patience. I make my motto the graffiti scrawled on a wall on Rue de Seine in 1953 by Guy Debord: ne travaillez jamais3. Conversely, as long as it feels like fun, I can spend days and nights on what turns out to be a useless task. Speed is essential; waiting fifteen seconds for an answer is completely different from waiting two minutes. In my opinion, creativity is in good part quantitative. Try more things in your mind and one will work. But the machine has to keep pace, and now it finally does. Expect miracles.

[Editor’s note: Though the presence of semicolons, en- and em-dashes may seem evidence to the contrary, LT does not use AI to write or edit this Substack. He happens to be married to an editor. TS]

My physicist friends are always amazed when I tell them that the names of biology Nobel winners are frequently unknown to the majority of biologists. That does not happen in physics.

It coyly claims it doesn’t use the best and completely illegal repository sci-hub, into which all scientists dip daily.

Never work. Debord was in most other respects a condescending twerp.

I love this piece even though AI, but not punctuation, scares the beJesus out of me. Re your piece: "I pay AI a small monthly sum and can access all the expertise I want at all times of the day and night. I have not yet paid for an AI site, even though my answers to questions mostly come in from Google and less and less rarely from Chatgpt. As per your statement: "However, I miss both the food and the sense of awe that comes from talking to someone whose life may have been very different from mine, but who nevertheless lives in the Republic of Ideas." Oh, how I agree! I am part of a discussion group that's been going on now for over a decade, mostly intelligent folk (tho not all per our weird invitation process), and still I don't find the intellectual discourse sufficient. I don't say this because I'm vastly intelligent. I'm probably about average, just more creative than some. But I rejoice in stimulating conversation. As I wrote in the play you helped me with, I find long, philosophical conversations the best foreplay. May I share this piece on FB or would you rather I just send it to a few select friends?

First chapter of Guy Debord’s society of the spectacle - ‘abstraction perfected’ is about Beyond Paradise btw